Listen to the article

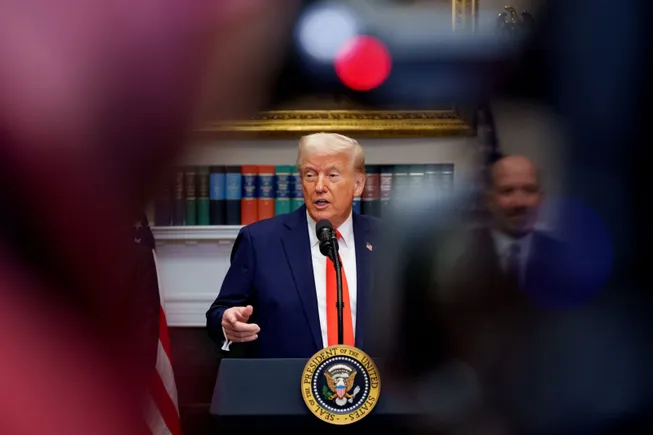

Healthcare companies struggling to adopt artificial intelligence amid a lack of federal standards are unlikely to get any help from the Trump administration, placing the burden of responsible implementation squarely on the industry’s shoulders.

That mandate is becoming increasingly difficult as the technology grows more complex, experts said during the HIMSS healthcare conference in Las Vegas.

“One thing that’s clear is that this administration is not going to regulate AI. Good or bad, take that for what it is,” Tanay Tandon, the CEO of provider automation company Commure, said during a panel.

President Donald Trump’s hands-off approach to AI governance means hospitals turning to the tools to save money and give overworked clinicians some relief will likely be operating in a regulatory gray area for at least the next four years.

The president says his goal is to free up U.S. developers to innovate. But that comes with downsides for tech developers and healthcare companies desperate for guardrails given AI’s proclivity to make mistakes, degrade over time and exacerbate existing bias.

Not to mention, a lack of national standards might actually hamper AI development and adoption, according to some experts.

“When there isn’t a federal framework, it can just absolutely cause all kinds of problems,” said Leigh Burchell, the chair of the Electronic Health Records Association. “We all just want to know what our rules are. And then we can comply.”

Biden versus Trump on health AI

To date, a handful of federal agencies, including the HHS’ technology office, the CMS and the Food and Drug Administration, have published targeted rules around the use and quality of AI in healthcare. But neither Congress nor the executive branch have zeroed in on a comprehensive framework to regulate the models — despite some progress during the Biden administration, when an HHS task force was working to build a unified regulatory structure.

That task force unveiled a strategic plan in January — just 10 days before Trump’s inauguration. However, Trump nixed the blueprint in one of his first executive orders.

Meanwhile, federal employees working on AI oversight, including at the FDA, have been caught up in the Trump administration’s purge of the government’s workforce. Amid the turmoil, the future of the HHS office that oversees AI policy remains unclear.

As a result, what little momentum there was in Washington to create a concrete strategy for overseeing health AI appears to have stalled out, at least for now. In its place, Trump has announced the Stargate Project, a $500 billion investment deal with private companies to prioritize AI development and maintain U.S. supremacy in the space — a high-stakes bet that was immediately complicated by the release of DeepSeek, a high-performing and inexpensive open source model from China.

“The current administration — the brakes have come off and the accelerator has come down.”

Brian Spisak

Program director of AI and leadership, Harvard University’s National Preparedness Leadership Initiative

The Trump administration did issue a request for information in early February to get public input on a potential national AI action plan. However, the plan’s wording makes clear the administration’s priorities: to “sustain and enhance America’s AI dominance, and to ensure that unnecessarily burdensome requirements do not hamper private sector AI innovation.”

The revocation of the Biden-era AI plan was largely symbolic, as agencies hadn’t yet gotten around to imposing any requirements on developers or users.

But in “the current administration — the brakes have come off and the accelerator has come down,” said Brian Spisak, program director of AI and leadership at Harvard University’s National Preparedness Leadership Initiative, at HIMSS. “There’s a lot of responsibility to leadership of health systems to find the optimal balance between innovation and speed and safety and tradition.”

A technological sea change

That responsibility — which also rests on AI developers creating the models, software vendors weaving them into health records and the clinicians using them — is not negligible.

Currently, even the most futuristic AI at healthcare institutions is being used to automate administration, and only peripherally touches patient care. But that appears to be changing: There’s growing interest among medical organizations in more clinical use cases for AI, like tailoring treatment plans or helping clinicians arrive at a diagnosis, according to a survey from HIMSS conducted in the fall.

Many of those use cases involve generative AI, which can create original text and images. But such models are known to hallucinate, or provide answers that are factually incorrect or irrelevant. AI can leave important information out, an error known as omission. Models can also drift, a term for when an AI’s performance changes or degrades over time.

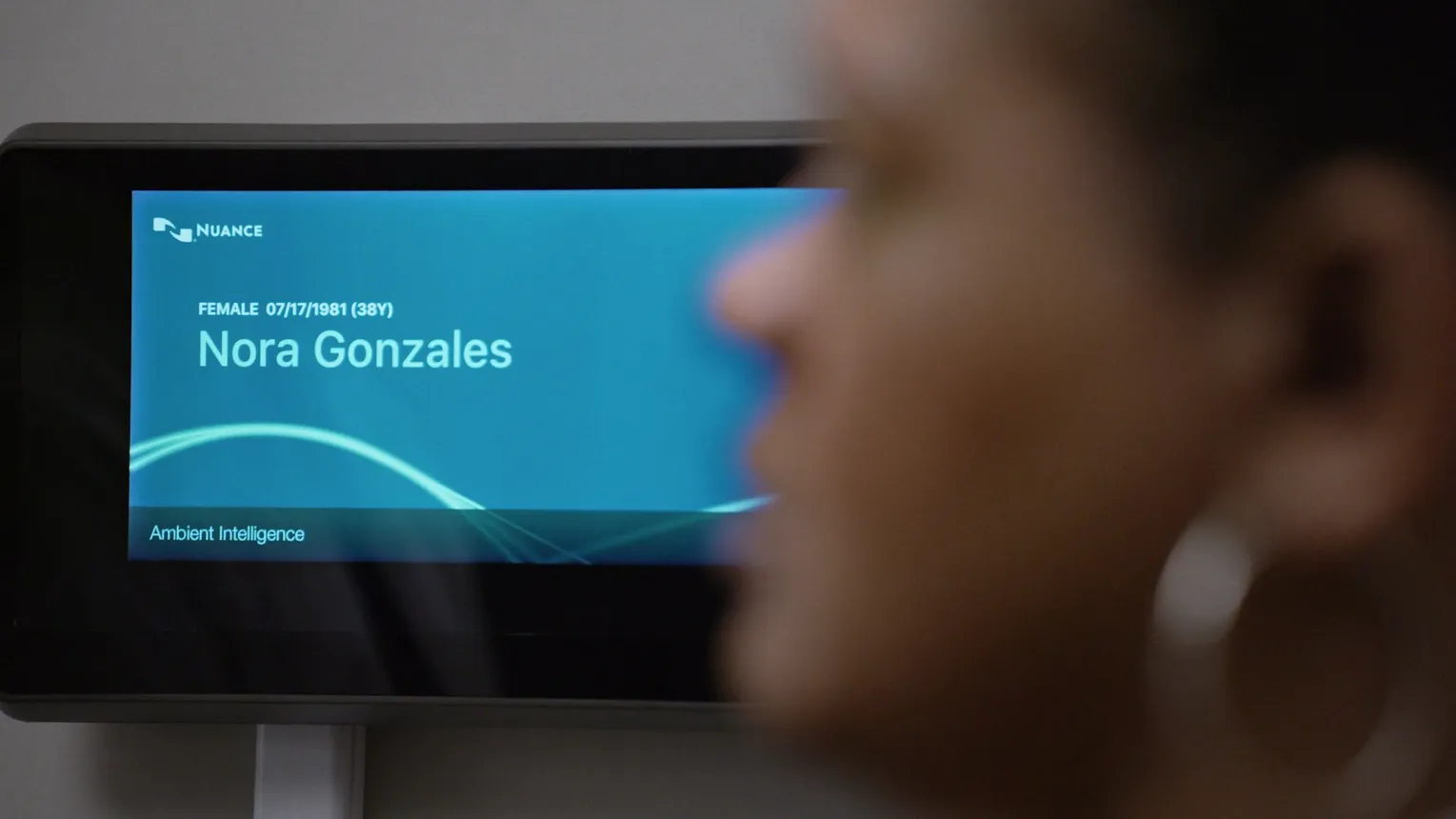

Given the increasing prevalence of AI in pulling data from EHR systems, transcribing doctor-patient visits and more, errors like these could interfere with clinicians’ ability to care for patients, experts say.

Meanwhile, the technology is advancing at a stunning rate. Last year, the healthcare industry was just beginning to come to terms with governance for generative AI. But now, the conversation has already moved onto AI agents, which can complete complex tasks largely unsupervised by humans.

The HIMSS health IT conference in March in Las Vegas, where a number of companies touted AI agents.

Courtesy of HIMSS

Commure’s Tanay equated the current moment to when America moved from kerosene to electricity at the end of the 19th century.

“The way that we did things six months ago is completely irrelevant,” he said.

Because of the breakneck speed of development, federal standards from any administration would likely need to be flexible, experts say.

The Biden administration’s HHS task force suggested the government could create guidelines around testing and piloting tools, along with some support for adoption. However, it shied away from a prescriptive approach.

That’s in line with the wish list from many stakeholders. Numerous executives at tech companies and hospital systems said any federal standards should be stratified by the level of risk an AI model imposes — for example, stricter oversight for algorithms that help doctors diagnose diseases, and looser restrictions for algorithms that help hospital staff allocate patients to beds.

“We have to weigh the balance between underregulation, which can potentially increase risk, and overregulation, which will stunt innovation,” said Anthony Chang, the chief intelligence and innovation officer at the Children’s Hospital of Orange County in California, during a panel.

“The current administration is more likely to be on the underregulation side. So we have to be careful as a profession that we don’t allow that to happen,” Chang said.

States, industry groups filling the void

The lack of a playbook from Washington has left hospitals and medical groups scrambling to build their own internal controls amid a patchwork of state laws and voluntary standards released by industry groups.

States including Colorado, Utah and California have already enacted legislation establishing disclaimer requirements for AI systems. More states are considering similar laws: The Electronic Health Records Association is tracking 150 different state bills related to health AI, according to Burchell.

“There is a massive explosion of bills,” Burchell said.

But differing standards could stop health AI developers and software companies from rolling out products in specific states, potentially disadvantaging patients depending on where they live. More risk-averse software companies may avoid AI, or certain states, altogether, she added.

“Legislation of a lot of sizes and shapes at the state level is a risk to us, because it means we have to do all kinds of different development. We would rather develop one system that can be used broadly and accepted across the country,” Burchell said.

Health AI standards groups are also stepping into the gap left by the federal government. The groups — often made up of leading hospitals, digital health companies and tech giants — include the Health AI Partnership, an AI learning network for the industry, and the Coalition for Health AI, which recently launched an AI registry for hospitals.

”I think we’ll probably see more of these non-government organizations like Health AI Partnership and some of those emerge as maybe our north stars today, as here’s some leadership in the space,” said Rachel Wilkes, the corporate lead for generative AI initiatives at EHR vendor Meditech.

But standards from industry consortia hold little weight without the heft of the federal government behind them, experts say. Historically, voluntary standards aren’t particularly effective.

“There’s room for people to act in their own best interest, whatever that may be, without any sort of federal framework,” Wilkes said.

‘We still don’t quite know how to deal with it’

EHR vendors and hospital operators say they’re building up rigorous internal standards for AI tools, including validation and frequent auditing.

“Government oversight has its place, but I do think the way that clinical practice evolves tends to be more driven by what’s happening at a health system,” said Seth Howard, the executive vice president of research and development for Epic, the largest EHR company in the U.S.

In interviews, executives with Epic, Oracle, Meditech and eClinicalWorks said they’re making AI available to doctors with rigorous oversight, including back-end accuracy checks and ongoing monitoring.

However, tech leaders stressed that it’s also the hospital and the clinicians’ responsibility to make sure everything is working as planned.

“We are working in an industry that deals with human life. It cannot be trivial. It cannot be under-exaggerated on what guardrails and checks and balances and what discussions need to happen,” said Girish Navani, the CEO of eClinicalWorks.

Technology behemoths betting heavily on AI feel similarly. Google, for example, has worked with for-profit hospital giant HCA on an evaluation framework to catch any errors generated by its AI models and ensure their reliability, according to Aashima Gupta, the head of healthcare for Google Cloud.

“We provide those tools for an evaluation framework, and for all of this there’s a human in the loop capturing the feedback, and that feedback loop then makes the model more effective,” Gupta said. “That’s what gives me comfort.”

“We are working in an industry that deals with human life. It cannot be trivial. It cannot be under-exaggerated on what guardrails and checks and balances and what discussions need to happen.”

Girish Navani

CEO, eClinicalWorks

Though some in the private sector say they’ve got governance handled, modern AI is incredibly hard to oversee, according to AI engineers. The main advantage of generative AI — its creativity — also introduces subjectivity, making grading its outputs complicated.

For example, if two clinicians are tasked to summarize a patient’s medical history based on clinical notes, their results could be incredibly different, albeit still accurate. It’s the same with generative AI, experts say: How do you measure quality in a standardized way when there’s that degree of variability?

“AI governance is still very much a maturing process,” said Harvard’s Spisak.

Hospital executives say they’re tackling oversight carefully. But some research suggests governance systems for simpler predictive AI models already aren’t rigorous enough. Hospitals with explicit procedures for the use and assessment of AI tools are still struggling to identify and mitigate problems, according to a study published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine.

A patient receives an exam in a room equipped with ambient listening AI technology to transcribe the interaction.

Permission granted by Nuance Communications

Even some of the most well-resourced and tech-savvy systems are struggling.

The Cleveland Clinic has an AI governing body that includes stakeholders from across the academic medical center, according to Rohit Chandra, the Cleveland Clinic’s chief digital officer. The task force oversees AI’s impact on the organization’s patients and workers while ensuring clinical safety and discussing thorny questions of privacy, legality and bias.

But “I don’t think we’ve figured it all out,” Chandra said during a panel. “The term hallucination, for one, has just shown up in the last two, three years. And we still don’t quite know how to deal with it.”

Hospitals should try to make specific people accountable for the performance of the tools, as part of a larger governing body that includes executives, lawyers, doctors and nurses, according to Brenton Hill, the head of operations at standards group CHAI.

Hospitals need to decide how to monitor AI effectively and report that information, which can depend on the products they have in place. They also need to consider what resources the AI will use and develop appropriate data use agreements with AI vendors, Hill said during a panel.

But “there’s not one silver bullet governance structure that you can put out there that will solve all your problems,” Hill said.

‘A pipe dream’

Though a road map from federal regulators would be helpful, stakeholders working to integrate AI tools into healthcare said they’re not holding their breath.

“While self-regulation is good, we don’t believe that’s sufficient. We believe AI is too important not to be regulated,” said Google’s Gupta.

But when asked what she expects from the Trump administration, Gupta was noncommittal. “It’s hard to say at this point. We are trying to figure out how we best work with them, share our best practices with them … Too early to say. I think the entire healthcare community is waiting for that,” Gupta said.

Other experts said the Trump administration is a wake-up call for hospital executives who believed Washington could assume responsibility for overseeing AI.

Instead, the mandate should be on everyone touching the technology to ensure AI algorithms — given their shifting nature and innate opacity — perform as they’re designed, especially in an industry where any mistakes could impact patient health.

“The easy answer is, if this regulatory body says it’s safe, then I can trust it. I think people were hoping that might happen for AI,” said Aaron Neinstein, the chief medical officer of agentic AI company Notable. “I think that was a pipe dream.”