According to Brad Stone, author of The Everything Store, there are two reasons to write a business book. You’re writing a thriller or a how-to manual.

In “The Nvidia Way,” veteran technology journalist Tae Kim does both.

Kim is responsible for Nvidia, which grew from a three-man graphics chip startup in the ’90s (one of countless companies in a crowded and cutthroat field) to one of the largest and most influential computer companies in the world. It illustrates the impossible origin of

Kim also explains the reasons for Nvidia’s success. It’s not just that we have talented leaders, great timing, and industry-leading technology.

Nvidia was successful because it cultivated a unique culture of excellence, which he called the “Nvidia Way.”

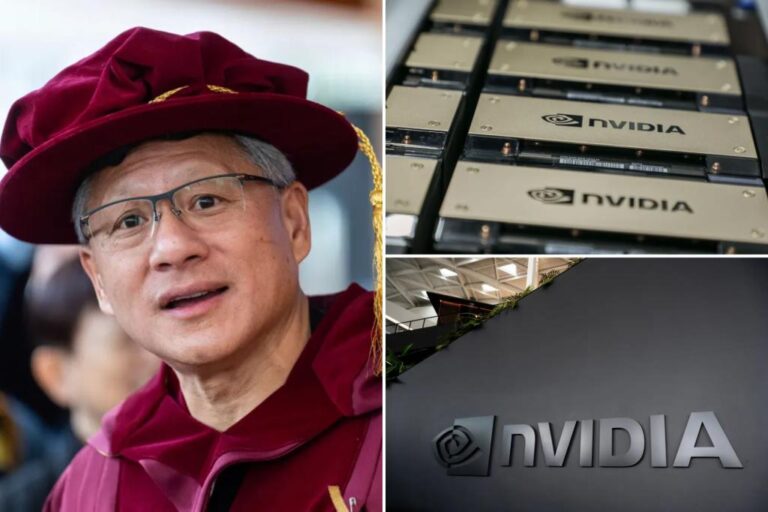

At the center of this story is CEO Jensen Huang, described in the book by one employee as a “very persuasive and very hard-working” leader. He has led the company since its founding in 1993 and has shaped its culture.

Huang is one of the longest-tenured CEOs in the technology industry and one of the few lone founders still running the show.

As Kim is quick to admit, the Nvidia Way is actually the Jensen Way. He sets the culture.

What is the Nvidia Way? First, we hire great people.

When in doubt, look for raw talent over experience. Second, reward performance and reward top talent well. Third, we always demand excellence and accountability from everyone, starting at the top.

Huang is an immigrant from Taiwan who excels at math and table tennis and graduated from high school at age 16.

He later became friends with Nvidia’s other co-founder, Curtis Priem, in Silicon Valley’s close-knit community. Curtis Priem also started programming computers in high school. I also became friends with Chris Malakowski, who realized halfway through his MCAT exam that he didn’t want to be a doctor.

Over many coffees at a local Denny’s, they convinced each other to quit their jobs and start a new company. Mr. Huang has been CEO from day one.

Priem and Malakowski are interesting characters and we get to know them a little bit, but if NVIDIA’s story is the Avengers, fans are the star of the show: Iron Man.

Nvidia launched at “perfect timing,” Kim says. By 1993, demand for graphics chips that powered video games like “Doom” exploded.

However, despite favorable market conditions, Nvidia’s first chip, the NV1, failed.

“People don’t go to the store to buy a Swiss Army knife. They get it for Christmas,” Huang later said of the product, which was fatally over-engineered.

“When we were young, we screwed up a lot of things,” Huang said, adding that Nvidia might have done better without him in the first five years.

The new chip RIVA 128 saved the company. Nvidia also made a small profit in its first year. This success would not last long.

The next five years were marked by both great victories and great setbacks. “Starting a company is a new skill,” Huang admits.

Nvidia often fell behind early on. Graphics cards took more than a year to design and launch, but with chip buyers updating their PC lineups every six months, no company could stay on top.

Huang’s solution: “We’re going to fundamentally restructure our engineering department to align with our refresh cycles.” This decision marks a shift in the chip industry as other competitors are forced to keep up or lose out. .

Fans call this “traveling at the speed of light.” This is the theoretical limit on how fast something can move in order to win. The “Star Trek” fan made headlines when he called this fast-paced culture even more maniacal, “mycelium spore drive.”

A few years later, Nvidia began to grow by leaps and bounds, going public in 1999 and then winning a deal from Microsoft for the original Xbox.

Nvidia then acquired 85% of Apple’s entire line of computers.

As the company became more successful, Huang became obsessed with the “innovation dilemma,” a concept coined by Professor Clayton Christensen. This concept explains how established companies are often disrupted by nimble startups.

Huang’s fear of being disturbed is what drives him. “The only thing that lasts longer than our products is sushi,” he likes to joke. That’s why he insists on erasable whiteboards, which he calls “the belief that successful ideas, no matter how great, are eventually erased and new ideas have to pick up the pace.” It represents.

Nvidia’s first real killer product was the graphics processor unit (GPU), released in 2003.

GPUs have changed market perceptions by placing GPUs (graphics engines) on par with the well-known CPUs, or central processing units. This was more than a marketing hype.

The new class of chips was programmable, which meant they could be used for countless use cases.

Initially, Nvidia had no idea how versatile GPUs actually were. Nvidia scientist David Kirk said, “This is truly the latest GPU. We stumbled across it.”

After all, the ultra-powerful graphics engine was perfect for other types of computation, including the nascent field of AI research. In fact, academics credit Nvidia’s GPUs with democratizing computing power and leveling the research playing field.

Huang recognized the opportunity in AI early on, declaring in 2012 that “we must consider this work as a top priority.”

To make it easier for non-graphics users to program GPUs, Nvidia created a software interface known as CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture).

Over time, CUDA became the company’s biggest asset. Once you get used to programming chips in one environment, you won’t want to leave.

Nvidia also began actively developing AI researchers through grants, joint ventures, and partnerships with academia. This decades-long effort helped effectively create a market for GPUs.

As Nvidia grew, it remained wary of corporate bloat and the inertia that kills companies. Mr. Huang dislikes corporate hierarchy. “A company should be as big as it needs to be to get the job done well, but preferably as small as possible.”

His goal is to fuse the Vulcan mind with his people (another reference to Star Trek), allowing them to share and anticipate each other’s thoughts.

Kim’s book leaves readers with the impression that the AI era has only just begun. Nvidia believes the entire data center market, which is largely made up of CPUs, will have to switch to GPUs, and chip purchases will exceed $1 trillion.

Nvidia’s “big bang” occurred in 2023, shortly after the release of ChatGPT, when the company exceeded revenue projections by a staggering $4 billion.

For some, Nvidia’s rapid rise to become the world’s largest company was a shock.

Their ultimate success should have been obvious to anyone paying attention, Kim argues.

“It’s Jensen’s personal will that has shaped Nvidia,” Kim said, asking what would happen if he and the company parted ways. That question remains unanswered. For now, Nvidia sits on an impregnable mountaintop, surrounded by a cultural moat that few can pass through.

Alex Tapscott is the author of Web3: Charting the Internet’s Next Economy and Culture Frontier and managing director of Digital Asset Group, a division of Ninepoint Partners LP.