Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

FT editor Roula Khalaf has chosen her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The computational “laws” that made Nvidia the world’s most valuable company are starting to break down. This is not the famous Moore’s Law, the semiconductor industry adage that says doubling transistor density every two years improves chip performance.

For many in Silicon Valley, Moore’s Law has been replaced as the dominant predictor of technological progress by a new concept: the “Law of Scaling” of artificial intelligence. This assumes that feeding more data into larger AI models requires more computing power and provides smarter systems. This insight has had a major impact on advances in AI, shifting the focus of development from solving difficult scientific problems to the simpler engineering challenge of building larger clusters of chips (usually Nvidia’s). did.

The law of scaling became clear with the launch of ChatGPT. The breakneck pace of improvements in AI systems in the two years since then suggests that this rule may remain true until we reach some kind of “superintelligence,” perhaps within the next decade. It looked like. However, over the past month, industry whispers have grown louder that the latest models from OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, and others are not showing the expected improvements in line with the predictions of their scaling methods.

“The 2010s were the era of scaling, and now we are back to the era of surprise and discovery,” OpenAI co-founder Ilya Satskeva recently told Reuters. A year ago, the man said he believed it was “very likely that the entire surface of the Earth would be covered with solar panels and data centers” to power AI.

Until recently, scaling laws were applied to “pre-training,” a fundamental step in building large-scale AI models. Today, AI executives, researchers, and investors agree that, as Marc Andreessen said on his podcast, the capabilities of AI models are “over the top” with just pre-training. This means that more work is required after the model is built to maintain progress. come.

Some early proponents of scaling methods, such as Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, have attempted to modify the definition. Advocates argue that the reduced benefits of pre-training don’t matter because the model is now able to “reason” when asked complex questions. “We are witnessing the emergence of new scaling laws,” Nadella said recently, referring to OpenAI’s new o1 model. But this kind of shenanigans should worry Nvidia investors.

Of course, the “law” of scaling was never an ironclad law, just as there was no inherent factor that allowed Intel’s engineers to continue increasing transistor density according to Moore’s law. Rather, these concepts serve as organizing principles for the industry and foster competition.

Nevertheless, the scaling law hypothesis fuels the “fear of missing out” on the next big technology transition, leading to unprecedented investment in AI by Big Tech. Capital spending at Microsoft, Meta, Amazon and Google is expected to exceed $200 billion this year and exceed $300 billion next year, according to Morgan Stanley. No one wants to be the last one standing in building a superintelligence.

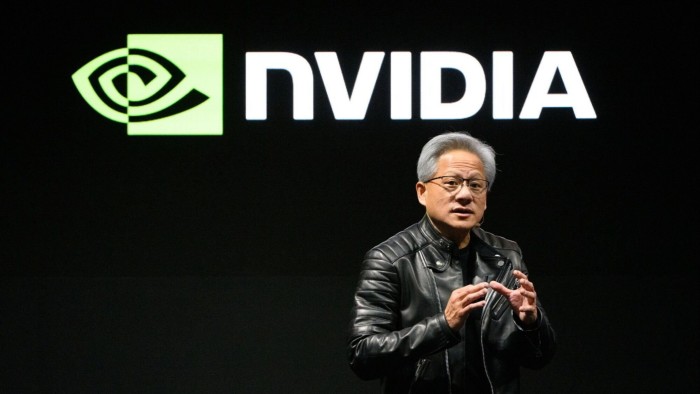

But once bigger is no longer better in AI, will those plans be scaled back? If so, NVIDIA will suffer more than other companies. When the chipmaker reported its earnings last week, the first question from analysts was about the laws of scaling. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang claimed that the pre-training scaling was “flawless,” but admitted it was “not enough.” The good news for Nvidia is that AI systems like OpenAI’s o1 have to “think” longer to come up with smarter responses, so this solution requires more chips for so-called “test time scaling.” Mr. Huang argued that it is about becoming.

Recommended

This may be true. So far, most of Nvidia’s chips have been absorbed by training, but as more AI applications emerge, the computational demand for processing capacity is expected to increase rapidly.

Those involved in building this AI infrastructure believe the industry will be playing catch-up in inference for at least another year. “Right now, this market needs more chips, not fewer chips,” Microsoft President Brad Smith told me.

But in the long term, the pursuit of chips to power ever-larger models before they can be rolled out is being replaced by something more closely tied to the use of AI. Most companies are still looking for AI killer apps, especially in areas that require o1’s early “reasoning” capabilities. Nvidia became the most valuable company in the world during the speculative phase of building AI. The scaling debate highlights how much its future depends on whether Big Tech companies can reap tangible benefits from these huge investments.

tim.bradshaw@ft.com