CNN

—

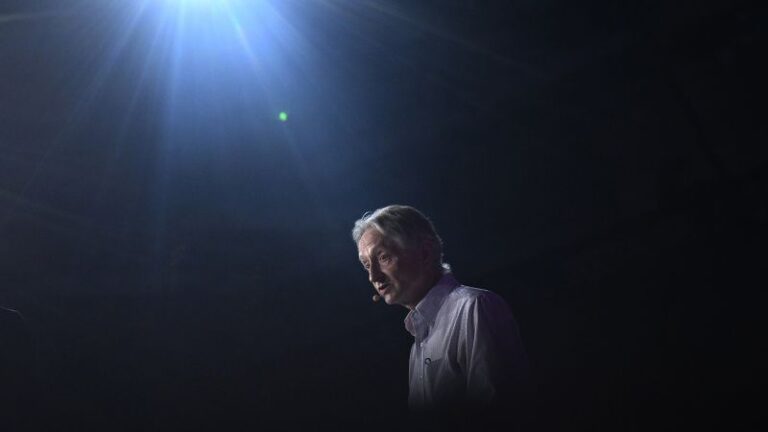

When computer scientist Jeffrey Hinton won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work in machine learning on Tuesday, he was quick to warn about the power of the technology his research is helping to advance: artificial intelligence.

“It will be comparable to the industrial revolution,” he said shortly after the announcement. “But instead of surpassing people in physical strength, we will surpass them in intelligence. We have never experienced what it is like to have something smarter than us. ”

Hinton famously left Google to warn of the potential dangers of AI and has been called the godfather of the technology. Now at the University of Toronto, he shared the award with Professor John Hopfield of Princeton University for “fundamental discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.”

And while Hinton acknowledged that AI could transform some parts of society for the better, leading to “significant increases in productivity” in areas such as healthcare, for example, he said, ” He also emphasized the possibility of many negative outcomes, especially threats. These things are out of control. ”

“I fear that the overall result of this is that systems that are more intelligent than us will eventually take control,” he says.

Hinton is not the first Nobel laureate to warn about the risks of the technology he helped pioneer. Here’s a look at others who have issued similar warnings about their own work.

The 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was jointly won by the husband and wife team of Frédéric Joliot and Irene Joliot-Curie (daughter of laureate Marie Curie and Pierre Curie) for the discovery of the first artificially produced radioactive atom. It was done. It was research that not only contributed to important advances in medicine, including cancer treatment, but also contributed to the production of the atomic bomb.

In his Nobel Prize acceptance lecture that year, Joliot concluded with the warning that future scientists “will be able to create explosive transmutation, veritable chemical chain reactions.”

“If such a transmutation were to succeed in diffusing within matter, you could imagine a huge release of usable energy,” he says. “But unfortunately, if the infection spreads to all elements of the planet, the consequences of unleashing such a cataclysm can only be viewed with alarm.”

Nevertheless, Joriot predicted that this would be “a process that[future]investigators will definitely try to accomplish while taking the necessary precautions.”

Sir Alexander Fleming shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Medicine with Ernst Chain and Sir Edward Florey for the discovery of penicillin and its application in the treatment of bacterial infections.

Fleming made his first discovery in 1928, and by the time he gave his Nobel Prize lecture in 1945, he had already issued an important warning to the world. They were enough to kill them, and something similar happened inside their bodies from time to time,” he said.

“There may come a time when penicillin is available for everyone to buy in stores,” he continued. “And there is a risk that an uninformed person could easily overdose, exposing microorganisms to non-lethal doses of the drug and developing resistance.”

Dr. Jeffrey Garber, an infectious disease physician and medical director of the antimicrobial stewardship program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said this was “a very important and visionary idea for many years.” .

Nearly a century after Fleming’s initial discovery, antimicrobial resistance (resistance of pathogens such as bacteria to therapeutic drugs) is considered one of the greatest threats to global public health, and in 2019, according to the World Health Organization. 1.27 million people died. Alone.

The important part of Fleming’s warning may have been the excessive and widespread use of antibiotics, rather than the idea of low doses.

“Antibiotics are increasingly being administered completely unnecessarily,” Gerber told CNN in an email. “Increasingly, we are seeing bugs that are resistant to almost every (and in some cases all) antibiotics we have.”

Paul Berg, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980 for the development of recombinant DNA, a technology that helped revitalize the biotechnology industry, has issued as harsh a warning as any other laureate about the potential risks of his research. did not emit.

But he acknowledged concerns about the potential of genetic engineering, including biological warfare, genetically modified foods, and gene therapy, a form of medicine that replaces defective disease-causing genes with functioning ones.

In his 1980 Nobel Prize lecture, Berg focused specifically on gene therapy, saying that this approach “has many pitfalls and unknowns, including the feasibility of treating specific genetic diseases, not to mention the risks.” There are questions about feasibility and desirability.”

“It seems to me that if we are to proceed along these lines, we will need a more detailed knowledge of how human genes are organized, how they function, and how they are regulated. I think so,” he continued.

In an interview decades later, Berg said that scientists in the field had already spoken publicly in 1975 at a conference known as Asilomar to recognize the potential dangers of the technology and address guardrails. He said he was rallying with the others.

“Concerns about recombinant DNA and genetic engineering came from scientists, and that was a very serious fact,” he told a science writer in 2001, according to a transcript posted on the Nobel Prize website. He told Joanna Rose of

Berg said that by publicly acknowledging the risks and the need to examine them, “we have won so much public admiration and tolerance, so to speak, that we now have to ask ourselves, how can we prevent the risks? “We were allowed to actually start tackling the issue.” Will anything dangerous come out of our work? ”

By 2001, he said, “the experience and experiments that had been done showed us that the initial concerns we had that we believed were really possible actually did not exist.”

Gene therapy is currently a growing field of medicine, with treatments approved for sickle cell disease, muscular dystrophy, and some forms of inherited blindness, but it remains complex to administer and prohibitively expensive. yeah. In the early days of this technology, the technology killed 17-year-old Jesse Gelsinger in a clinical trial in 1999, raising ethical questions about how the research was conducted and halting research in this field. was late.

And although Berg himself expressed concerns, he ended his 1980 Nobel Prize speech with a call for optimism and “the need to move forward.”

“The breakthrough in recombinant DNA has provided us with new and powerful approaches to problems that have intrigued and vexed humanity for centuries.” he said. “I will not be daunted by that challenge either.”

Four years ago, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuel Charpentier shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing a genome editing method called CRISPR-Cas9.

In his talk, Doudna detailed the “extraordinary and exciting opportunities” for technology across public health, agriculture, and biomedicine.

However, she said research needs to proceed more carefully when applied to human germ cells, where genetic changes are passed on to offspring, compared to somatic cells, where genetic changes are limited to that individual. .

“Heritability makes germline genome editing very powerful, given its use in plants and for example to create better animal models of human disease. “It’s a great tool,” Doudna said. “The situation is very different given the enormous ethical and social issues raised by the potential use of germline editing in humans.”

Doudna, who founded the Institute for Innovative Genomics, told CNN this week that it is an important responsibility for scientists to properly warn about the potential for misuse of their discoveries, especially when their research has far-reaching implications for society. “I believe that this is a useful public service,” he said.

“Those of us closest to the science of CRISPR understand that while this is a powerful tool that can positively transform our health and the world, it can also be used for potentially nefarious purposes. ” she said. “We have seen that its dual-use capabilities can be used in conjunction with other innovative technologies, such as nuclear power, and now with AI.”

CNN’s Christian Edwards and Katie Hunt contributed to this report.