As I was scrolling through X (erm, I deleted the app so I’m now viewing it on my phone using a browser), a post by Farhad Manjoo caught my eye.

It’s a screenshot of a photo of five older men dressed like military veterans sitting on an airplane, with the words “Real heroes don’t exist in Hollywood” written underneath the photo.

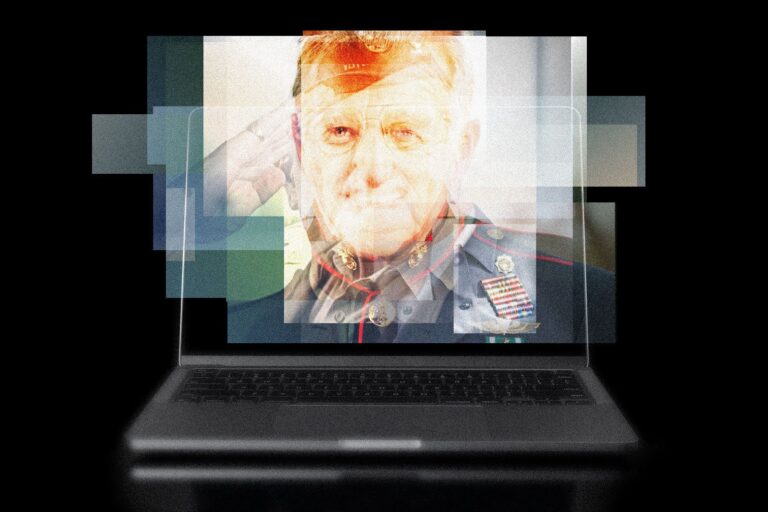

Look a little closer and the clumsy AI seems to be screaming: What commercial airliner has five rows of seats next to windows? God knows what military it belongs to? It has an eagle and stripes but no stars. What writing is on its hat? It’s not English, and it’s not in any human language.

Manjoo copied the bizarre image from somewhere on the internet and added the comment: “We should honour these men. Look what the war has done to them.”

We should respect these men. Look what the war has done to them. pic.twitter.com/f8DgPEnsqS

— Farad Manjoo (formerly Blue Check) (@fmanjoo) August 22, 2024

But the extra finger, the manjoo joke, the meaningless hat, and the five seats in the row aren’t what told me this image was fake. Look, the man sitting in the seat closest to the “camera” is my father. He passed away 14 years ago.

It gave me pause. I wanted to know where this image came from. I mean, I already knew to some extent, and I also knew that there would be no way to know for sure. In our new reality of a vast amount of untraceable digital plagiarism that wasn’t made by us, but was made of us, I feel it’s very hard to know anything for sure.

Earlier this summer, while running breathlessly along Oregon’s rugged Pacific coast, I was startled by a ghost. It was my father, standing on a cliff, holding binoculars to his face and gazing out to sea. Everything about him was characteristic of him: plaid shirt, khaki hiking pants, brown hiking boots, even a silly brimmed hat. But I ran further, closer, and of course it wasn’t him, just a regular bearded old man with binoculars, maybe someone’s father.

Grief is a strange thing in that way. Sometimes you stumble on a street corner, or your reflection startles you, because for a split second it seems like one of the people you lost has returned. You find someone you lost.

My father decided a few weeks before he died of prostate cancer that he wanted to be buried in a cemetery in the woods. He visited the cemetery and said it was a nice enough place, but he passed away before the arrangements could be made.

My father had converted to Islam a few years before his death, so my brother, tasked with making the final preparations within a tight deadline, described to me the somewhat surreal scene of the morning after my father’s death, standing in a small woodland in the English countryside, talking on his flip phone to a man whose smartphone was using an app to find the qibla. While my brother and the man on the other end of the phone triangulated to find a clearing facing Mecca, a worker at the burial ground expressed concern about whether the shroud they would use to wrap my father’s body was fully biodegradable.

I missed the final weeks of my dad’s life, the grave search, the funeral. I was confined to my home during the final stages of my pregnancy, the birth, and the first days with my daughter, his first grandchild. I was at a breastfeeding support group in New York City while he was buried under a crooked beech tree in Beaconsfield, England. We didn’t do a virtual funeral in 2010.

After seeing the awkward AI image of my father, I emailed Farhad to ask if he knew where it came from. I assumed he’d gotten it from a Reddit forum, but couldn’t remember the exact link. I did a reverse image search and found that the image was floating around. As far as I could tell, it was first posted on a meme forum called America’s Best Pics and Videos by a charming account with the handle “ViperEnforcement.” Comments on that original post were full of people praising the service of the men in the photo, calling them true patriots and thanking them for giving us our freedom.

I (like most people) do not have a degree in advanced AI forensics. In this case, the pinnacle of my technical investigative skills is “reverse image search.” Since this is not something available via FOIA, I can only speculate as to the origin of the image. I suspect that the image generator scraped a photo of my father from somewhere online (maybe a wedding photo I posted in 2007?) and did not blend it enough to turn it into a new person. Instead, it spit out an eerie duplicate.

But this isn’t a bereaved family member’s second look. This isn’t some bearded old man shooting for the cliffhanger. This is a stolen second look, exhumed from his father’s years-old digital shadows and repurposed to adorn MAGA forums, reposted by Facebook patriots, and even used in fundraisers and puzzles.

We have handed over the keys to our once private, analog existence to the wealthiest corporations in the history of humankind. Our memories have become digital remains, forever to be absorbed, digested, and reanimated by machine learning. Our lives, our dead, and their data are becoming a kind of digital compost. Is it like a forest burial?

Well, we’re not. We’re not vegetable waste, and trees aren’t going to grow from my dad’s online remains. We all feel bad that our information is now completely out of our control. If we think about it for a moment, we might feel angry. But it’s impotent anger. There’s no place for it. It’s pointless.

I used to try to do something about it. Well, that was it. Remember those Facebook posts that were very common about 10 years ago? “Please repost this post and tell Facebook that you don’t agree to the use of your image.” It made no sense then. But I don’t even try anymore (well, maybe my aunt still does it). Nowadays, when faced with this question, I half click “Allow all cookies”. What’s the point? The secret is out of the bag. The unknown bigwigs “they” already know everything about me.

Derek Heckman

How a popular card game became embroiled in a bot controversy

read more

My father used to say to me, “A boy who knows his father is a wise boy.” I think his dad jokes were meant as a flippant intimation that I wasn’t his child. That’s the kind of person my father was. Someone I thought I knew, but didn’t. And he became even more like that after he died.

Our position and rights in this new world of artificial neural networks go beyond uncertainty and take on an element of unknowability. We are not smart. We don’t know where it all comes from. We can’t even prove that this photo of my dad is a photo of my dad. There are small differences, like the beard line and the shape of his glasses, but when I texted this photo to my siblings, they all replied with things like “wow” and “this is definitely my dad.”

At the same time, it certainly isn’t enough evidence to sue anyone, even if there is someone to sue. Who can sue? Who can give a cease and desist order?

Maybe writing this article will provide some relief? People can post links to this article at the bottom of their posts in online groups, forums, X-retweets (or whatever Elon wants to call it now), and we can correct the record. “Hey! There are real dead people in this fake photo!”

I could retract the story. I could tell him that my father wasn’t a U.S. veteran, but a Canadian, and that he was in fact a virulent anti-American, an oil engineer turned environmentalist and serial cheater. I could tell him his darkest secret: that he was a sexual abuser. A child molester. I could tell him the trail of pain and suffering and destruction he left behind. The unanswered, unanswerable questions. I could tell him that he was not a hero, but my deeply flawed father. A man I loved very much, and still love, in incredibly complicated ways, some simplified by his death, to be sure, and some more complicated by his artificial resurrection and reappearance in my timeline.

I could tell you all that, but who am I fooling? Nobody cares. You know what? It’s pointless.

Men have Instagram faces, too. Maybe corrupt gamblers can’t actually predict elections. AI made my dead dad into a meme. Who should I sue? Inside the heated debate that’s dividing the writing community.

I know all too well the feeling of wasted anger, the anger that is directed at no one. The extent of my father’s abuse was only revealed to me a little over a year after he was washed, wrapped and buried in the ground at the base of that beech tree.

But what do I do about this ghost in the photo, this non-consensual technological violation? I know this is nothing compared to the horror experienced by (mostly) women whose likenesses have been repurposed for porn, by people whose identities have been stolen, by people who have been catfished, scammed and tricked with AI-generated images and videos. This is not a deepfake that will destroy democracy. This image has not harmed me. My chance encounter with this image among all the rubbish flickering before my eyes in Black Mirror was just an everyday, banal trauma. An image of the all-too-common ghost of a family member haunting me as I rage at what is beyond my reach. The one I lost, I can never find again. In the end, this is just a weird photo of my dead person. father.