Without data on product sales volumes or average selling prices, it’s difficult to have an intelligent debate about whether NVIDIA’s $2.9 trillion valuation is justified.

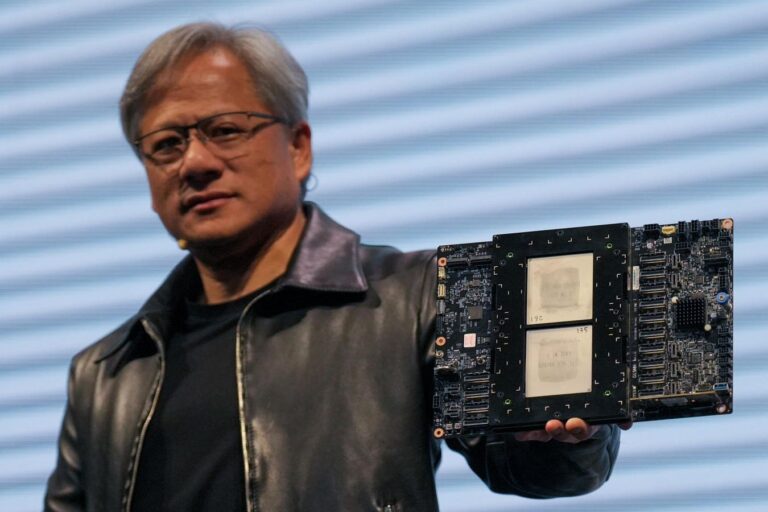

Taipei, Taiwan – 2023/06/01: NVIDIA President Jensen Huang holds the Grace Hopper superchip … (+)

SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

This semester, I am using NVIDIA as a real-world case in my classes. A key analytical tool I encourage my students to reflect on is the decomposition of a company’s revenue into the quantity of products sold (Q), the product mix sold (M), the selling price per unit of product (P), and the impact of foreign exchange (FX). This idea has its roots in the Apples-to-Apples studies done by Trevor Harris at Morgan Stanley in the late 90s and early 2000s.

Why break down revenue in this way? I often tell my students that Q is one of the best ways to incorporate company valuation into strategic business planning.

Netflix Q

To illustrate this point, let’s consider a simple example. Ignore M and FX for now. As of September 16, 2024, Netflix’s stock price is $702 per share. In the year just ended, Netflix reported annual EPS (earnings per share) of $12.03. Assuming a cost of equity of roughly 9% (assuming a Treasury yield of 3.65%, a beta of 1.1, and a risk premium of 5%), Netflix’s perpetually available earnings per share is $133 ($12.03/$0.09). This simple calculation shows that Netflix needs to increase its earnings per share by $58.2 in the future (($702-133)=$569*.09). This equates to an annual revenue increase of about $23 billion each year (450 million shares*$51). Now, back to Q. Netflix reported 278 million paid subscribers as of July 2024. This means the company would have to generate an additional $83 in profit per subscriber each year ($23 billion / 278 million subscribers). That’s $83 in revenue (not profit), or about $7 in profit per month. Is this feasible, given that the US and Canadian markets (about 76 million subscribers) are likely saturated and are perhaps the single most insensitive to price increases?

The more important point is that we can at least have a data-driven strategic conversation about Netflix’s valuation. Most of the analyst and boardroom conversations revolve around revenue growth (g). I don’t think abstract comments about the growth rate (g) built into the valuation are very useful. How do we adjust g? What does that mean for Netflix’s strategy and its chances of achieving that growth rate? The conversation around Q is much more insightful to me.

So what does this have to do with NVIDIA?

NVIDIA

Well, NVIDIA doesn’t release quarterly earnings. Consider the data. As of September 16, 2024, NVIDIA is trading at $118 per share. I would normally benchmark this against last year’s EPS, but NVIDIA is a special case, with revenues for the first two quarters of this year being as high as revenues for all of last year. Cumulative EPS for the first half of this year is $1.29. Let’s simply extrapolate this to a year ($2.60). Assuming a cost of equity of about 13% (assuming Treasury yields of 3.65%, beta of 1.8, risk premium of 5%), the value of repeating this year’s projected EPS forever is $20 per share ($2.6/$0.13). This suggests that NVIDIA would need to earn an additional $12.74 ($118 – $20 = $98*.13), or effectively increase EPS to 6 times this year’s revenue. Is this achievable?

I then looked for Q and P, but found nothing. NVIDIA has three fast-growing segments (Data Center, Networking, and Automotive) and two stable segments (Gaming and Visualization). Here’s the most useful information from NVIDIA’s latest 10-K disclosure:

FY24 revenue was $60.9 billion, up 126% year over year. FY24 data center revenue increased 217%. Strong demand was driven by enterprise software and consumer internet applications, as well as multiple verticals including automotive, financial services and healthcare. Customers across industries are accessing NVIDIA AI infrastructure both in the cloud and on-premise. Data center compute revenue increased 244% during the fiscal year. Networking revenue increased 133% during the fiscal year. FY24 gaming revenue increased 15%. The increase reflects increased sales to partners as channel inventory levels normalise and demand increases. FY24 professional visualization revenue increased 1%. FY24 automotive revenue increased 21%. The increase primarily reflects growth in autonomous driving platforms.

Unfortunately, there is no discussion of how many Qs and Ps NVIDIA sells in one major segment (data center). How many GPUs (graphics processing units) does NVIDIA sell? How many more do they need to sell to reach their valuation? If you argue that they do something else, please clarify what that something is and how many Ps and Qs of that something they need to sell. Without this data, it is difficult to have an intelligent debate about whether NVIDIA’s $2.9 trillion valuation is justified.

Large sample evidence

In a recently completed paper, I and my co-authors (Srinivas Mahapatro from Rochester Institute of Technology, Prateek Manikpuri and Prasanna Tantri from the Indian Institute of Management) test a natural experiment in India where manufacturing companies were required to disclose product-level revenue and sales volumes in their audited financial statements from 1997 to 2011. We demonstrate that mandatory disclosure of volumes and product prices (i) reveals the persistence of a company’s sales growth, (ii) reduces information asymmetries between management and the market, (iii) reduces errors in analysts’ earnings forecasts, and (iv) reduces stock market reactions to earnings announcements.

The large sample evidence simply confirms the intuition that it’s very hard to bring valuation back into the strategic conversation unless we know something about a company’s Ps and Qs. In particular, is the stock market’s valuation of NVIDIA’s future consistent with how much of its products and services it will sell, how much it will price those products and services, and what we assume about the presence or absence of competition and the company’s cost structure (e.g., fixed costs don’t change much as Q changes within a certain range). Concrete data on Ps and Qs allows us to move from hypothetical speculation to an evidence-based conversation about the likelihood that NVIDIA will grow to its valuation.

As always comments are welcome.