Get your free copy of Editor’s Digest

FT editor Roula Khalaf picks her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

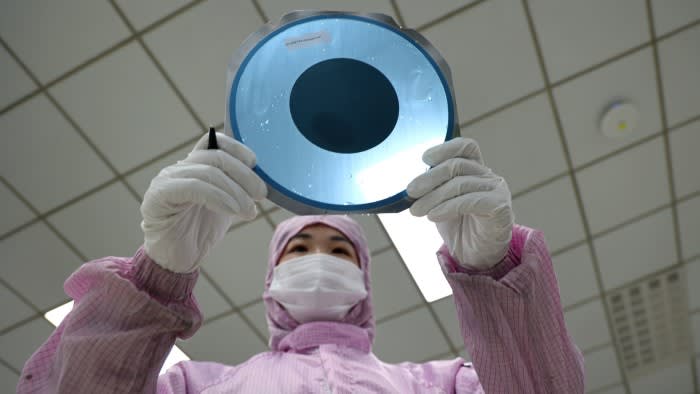

China’s export controls on critical semiconductor materials have hit supply chains and stoked fears of shortages in Western production of advanced semiconductors and military optics.

Chinese government restrictions on exports of germanium and gallium, which are used in semiconductors and military and communications equipment parts, have caused prices of the minerals in Europe to nearly double over the past year.

China introduced restrictions last year that it said were to safeguard “national security and interests” in response to U.S.-led restrictions on the sale of advanced semiconductors and semiconductor-making equipment.

These restrictive measures and subsequent export controls have highlighted Beijing’s dominance in the global supply of dozens of critical resources.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the country produces 98 percent of the world’s gallium supply and 60 percent of its germanium supply.

“The situation in China is critical. We are dependent on China,” said one person at a major consumer of semiconductor materials.

Analysts said the restrictions were a clear signal that President Xi Jinping’s government intends to target Western economic interests to counter restrictions on China’s access to cutting-edge semiconductors and other advanced technologies.

Officials at the affected companies said that while large shipments of Chinese gallium are still taking place, overall exports have fallen by about half since the restrictions were put in place.

“If China were to reduce its gallium exports, as it did in the first half of this year, our stockpiles would be depleted and we would experience shortages,” they said.

Jan Giese, senior manager of minor metals at Frankfurt-based Tredium, said the gallium and germanium the group was able to access through China’s new export license system was “just a fraction of what we had purchased in the past.”

“These export controls put an extra burden on everything outside of China and add further complexity to an already tricky market,” Giese said.

These two materials are essential for the production of advanced microprocessors, fiber optic products and night vision goggles, so production of these products could be disrupted if Beijing continues to restrict exports.

This month, the Chinese government also announced export restrictions on antimony, a mineral used in armor-piercing ammunition, night-vision goggles and precision optical instruments. The move comes after China restricted exports of graphite and technology used in the extraction and separation of rare earths.

Germanium prices in China have risen 52% since the beginning of June to $2,280 a kilogram, according to data provider Argus.

“China isn’t even supplying germanium overseas right now,” said Terence Bell, manager of Vancouver-based boutique metals trader Strategic Metals Investments.

Regulations for gallium and germanium mean each shipment needs approval, which can take 30 to 80 days, and the uncertainty makes long-term supply contracts unfeasible, traders said. Applications must specify the buyer and intended use.

Corey Combs, associate director at Beijing-based consulting firm Trivium China, said the Chinese government’s main motivation is to “send a signal” that it may retaliate against U.S.-led pressure on Chinese companies and critical industries.

“At the end of the day, the biggest reason (for the restrictions) is that if you want to block exports to a particular place, you can deny the licence,” he said.

Traders blame Chinese stockpiling for soaring prices of germanium, which is used to make advanced chips, fiber optic cables, solar panels and military thermal imaging cameras.

Giese said the amount of germanium in the stockpile is a matter of market speculation, but “the total amount at stake almost certainly represents a significant portion of China’s annual production.”

China’s Foreign Ministry declined to comment.

Trivium’s Combs said the Chinese government sees the export controls as a way to ensure domestic supplies of materials used in clean-energy technologies that are central to the country’s industrial upgrading.

Officials at the company, a major user of semiconductor materials, said China was using the restrictions to catch up with countries such as the United States that are more advanced in semiconductor technology.

“Assuming the global situation and U.S.-China relations remain as they are, we see no incentive for China to ease its export controls,” the person said.