Since the second half of 2020, the phones of tens of thousands of poor villagers in Togo have been sending good news as the Covid-19 pandemic began to get serious. Their money was ready. With the help of artificial intelligence (AI), these villagers on narrow lands in West Africa were authorized to receive around US$10 every two weeks and delivered directly to their mobile money accounts. That may not sound very much, but it can help people not get hungry.

Traditional poverty alleviation projects rely on data collected through face-to-face surveys. This was not possible during the pandemic. However, Togo’s efforts were called Nobissi, meaning “solidarity” in local Ewe, and incorporated AI to determine who should receive assistance. The project, led by Togo Minister of Digital Economy and Change, Sheena Lawson, will be working with scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, analyzing data from satellite imagery and mobile phone networks to analyze data from specific regions. and estimated individual wealth1. “We needed a surgical approach,” Lawson says. It was a critical moment for the use of AI in poverty prevention work, she says.

Around 700 million people around the world live in extreme poverty, defined by the World Bank as living on less than $2.15 a day. To end that poverty, one of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals, we need to understand who is in trouble and what their needs are. However, measuring poverty has been a challenge for a long time, primarily due to the time and cost of trying to gather data from the poorest and most vulnerable people.

Combining AI with citizen science to fight poverty

AI has allowed Lawson to leap the traditional hurdle of quickly making the most of their limited budgets using old and incomplete data. This is an approach that has gained both interest and controversy, and Joshua Blumenstock, a computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, collaborated with Nobisi.

AI tools aren’t just fast, says Ariel Benishey, a development economist at William & Mary’s Aid-Data Research Lab, a university in Williamsburg, Virginia, but it has a larger population and is more than a household survey. It can also include representative parts. and identify patterns of data that even experts may miss. AI may also help researchers assess how well they meet their goals and show how investments in areas such as health, agriculture, education, infrastructure will be rewarded. The World Bank recognizes this value and develops advanced AI tools to predict food crises and violent conflicts and to extract insights from the massive amounts of data collected after aid interventions. In October 2024, we concluded Poverty, Prosperity, and Planet Report 2.

But Olahore, a human geographer at Lund University in Sweden, who studies the intersection of AI and poverty, says there is a reason to be cautious. The AI model has been criticized as racist, sexist and otherwise biased. Just as household surveys often overlook the poorest families because they don’t have permanent housing, AI-driven programs may not help individuals who don’t have digital data trails, Hall says . They are not accurate enough to determine who is eligible for aid or cash grants and who is not, he says.

But flawed AI can be as bad as the current system of assessing poverty, Benyishay says. “Baselines are not complete data, they are actually very silly data,” he says.

Measurement of poverty

British social reformer Charles Booth took on early efforts to quantify poverty from 1886 to 1903 when he crossed his collection of data on cobblestones and social class in London. . He created a color-coded map of the city and reported his findings in a paper entitled Life and Labor of the People of London. British sociologist Seebohm Rowntree and his team interviewed 11,560 families in York, England, and published their findings in a 1901 book called Poverty: A Study of Town Life. The team calculated poverty based on a person’s ability to meet a person’s “physical efficiency” or minimal nutritional requirements. Minimal sample meals include bread, chopsticks, boiled bacon, potatoes, skim milk, and more.

After President Lyndon Johnson declared “war on poverty” in 1964, the Economic Opportunity Bureau adopted the poverty threshold conceived by economist Molly Oceansky, who took a similar approach. . Poverty was defined as the minimum income required to cover food, shelters and other basic costs. At about the same time, India made a similar calculation about the masses. Each expert tinkered with prescriptions to explain regional variation in rent and food costs, but all defined poverty based on the amount of money per day.

Dean Jolliff, an economist at the World Bank in Washington, DC, says the dollar per day approach is sluggish and easy to communicate. But how much money a person spends to get it is just one aspect of poverty. Economist and Anglican priest Sabina Alchia advocates for more nuanced ways to define poverty. “I want to know how many homes the poor are missing and how many poor people are leaving school, so I can actually deal with it in a very specific and direct way,” Oxford said. Alkaia, director of poverty and humanity, says development initiatives at Oxford University in the UK.

Mobile phone data can be used alongside satellite images and other data to estimate poverty across regions and countries.Credit: Kelvin Juma

In the early 2000s, Alkaia wanted a way to capture the various effects of poverty among people. Just because someone has enough money to buy food doesn’t mean they have enough for medical care or tuition, says Alkaia. In 2008, Alkia worked with James Foster, an economist at George Washington University in Washington, DC, to develop what is called the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) 3. This approach estimates a unified measure of poverty by aggregating deprivation and its strength, with a total of 10 indicators including nutrition, schooling, access to drinking water, and what households use for cooking fuels. I will.

For the field of poverty, this was a change in the ocean. Policymakers and others were able to measure, analyze and target interacting variables that contribute to poverty at the household level. The UN Development Programme replaced the human poverty index, focusing on survival, literacy, and Foster’s MPI in 2010, but certain UN agencies, along with the World Bank, relied on dollars per day. I’m continuing. meaning.

“It’s chaos”: US fundraising freezes put global health at risk

Researchers and aid agencies have developed countless methods other than MPI to define poverty. Jennifer Davis, who heads the Water, Health and Development Program at Stanford University, California, said these methods differ in factors that include depending on what you want to measure and what data is at hand. In a 2024 paper, a team led by Davis and her graduate student Christine PU evaluated four definitions of poverty used in the field, including daily spending rather than MPI, and those definitions were Ethiopia. We found a major difference in how we rank households. Ghana and Uganda 4. “When we conducted the analysis, we not only found no agreement on the complete sample, but we also found no urban households or lower 20% or lower 1%. Our biggest needs,” said PU. says.

In addition to the lack of agreement on definitions, there is only a matter of time. Even oiled field teams take hours to investigate a single family, Joliff says. Poverty researchers have improved metrics and incorporate modern calculation methods to analyze data, but in many cases they continue to rely on ground surveys to collect those data. Many people are surprised we are still doing family research, says Joliff. But “this concept that we have all the data about everyone is a very rich world perspective.”

Turning to AI

As a doctoral student in agriculture and resource economics, Marshall Burke was well versed in tedious data collection. To learn about the agriculture and agricultural practices of East Africa, Burke traveled to Kenya and Uganda, where he talked to farmers and walked through the fields. However, when Burke launched the Environmental Change and Human Results Lab at Stanford University in 2015, he wondered whether the computer revolution might offer a better approach.

These experiments can lift millions of people out of miserable poverty

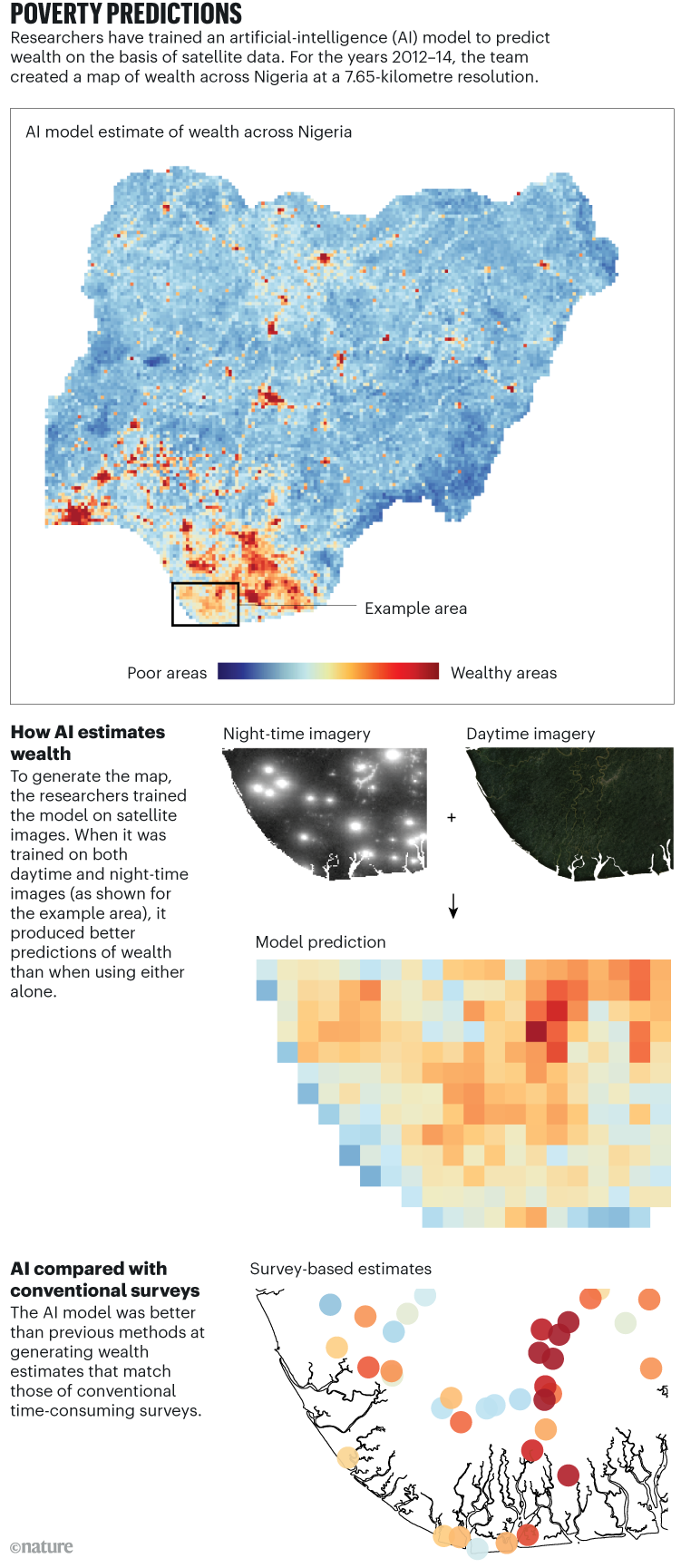

With extensive experience in remote sensing, David Robell occupied the office next to him. At about the same time, AI and image recognition expert Stefano Ermon also joined Stanford University. The trio’s discussion has turned into a way to help identify people living in poverty around the world using increasingly increasing data from satellite images. Knowing that nighttime lighting can become a rough proxy for wealth, researchers use night satellite images of African regions along with daytime images to teach computer models and features related to wealth I have identified the following.

Asking a computer to compare images of areas already known to be very rich or very poor is an electronic version of the game “Spot the Difference,” says Burke. The algorithm compares road distribution and state, amount of green space, building size and spacing, and many other variables. “Every kind you and I think we’ll look for in our image are a bit predictive,” Burke says. “The machine can sort all its data,” and decide which aspect is most relevant.

In 2016, the team reported that AI analysis of satellite images was strongly correlated with ground measurements of Poverty 5. As machine learning advances, Lobell, Burke, and Ermon improved their models by incorporating modern techniques.

Using the Pan Africa dataset of publicly available satellite imagery, TRIO tested an updated approach in May 2020. The algorithm was similarly performed when the team compared its machine learning predictions with wealth-related survey data from 20,000 villages. A painstaking investigation, but with effort and a small portion of cost6 (see Poverty Prediction).

Source: ref. 6

“This was a very important improvement concept for the development community,” says Benyishay. He says other teams are taking part in the experiment and throwing away many different ideas. Scientists apply machine learning to search for patterns in satellite imagery and mobile phone data, analyzing the impacts of drought, agricultural productivity, infrastructure investments, and more.