AI microchip supplier Nvidia is the world’s most valuable company by market capitalization, but it remains heavily dependent on a small number of anonymous customers who collectively contribute tens of billions of dollars in revenue.

The AI chip darling told investors in its 10th quarterly report to the SEC that it has very important major customers whose orders each account for a portion of Nvidia’s global consolidated sales. We warned again that we were exceeding the 10% threshold.

For example, an elite trio of particularly deep-pocketed customers individually purchased between $10 billion and $11 billion worth of goods and services in the first nine months that ended in late October.

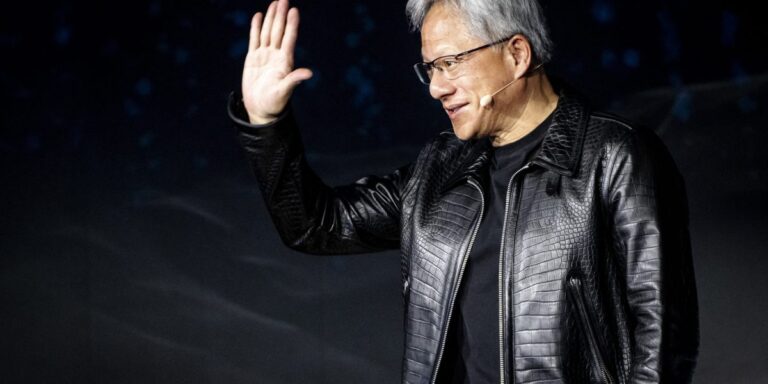

Fortunately for Nvidia investors, this isn’t going to change anytime soon. Mandeep Singh, global head of technology research at Bloomberg Intelligence, said he believes founder and CEO Jensen Huang’s prediction that spending will not stop.

“Even without any material setbacks, the data center training market could reach $1 trillion,” he says. At that point, Nvidia’s share will almost certainly drop significantly from its current 90%. But it still has the potential to generate hundreds of billions of dollars in annual revenue.

Nvidia remains supply constrained

Outside of defense contractors living off the Pentagon, it is highly unusual for a company to have such a concentration of risk in a handful of customers, let alone the first company worth an astronomical $4 trillion. Needless to say, companies that are trying to become

If you look at Nvidia’s financial results on a strictly three-month basis, there were four anonymous whales that together accounted for nearly every $2 of revenue in the second fiscal quarter. At least one of them has dropped out this time, and only three still meet that criteria.

Singh told Fortune that the anonymous whales likely include Microsoft, Meta, and possibly Supermicro. However, NVIDIA declined to comment on the speculation.

Nvidia refers to them only as Customers A, B, and C, and says they all purchased a total of $12.6 billion in goods and services. This represents more than a third of NVIDIA’s overall $35.1 billion recorded in the fiscal third quarter ending at the end of October.

Their shares were also split evenly, each accounting for 12%, suggesting that they were likely allocated the maximum amount of chips, rather than as much as they ideally wanted.

This would be in line with founder and CEO Jensen Huang’s comments that the company is supply constrained. Nvidia outsources the wholesale manufacturing of its industry-leading AI microchips to Taiwan’s TSMC and does not have its own production facilities, so it cannot simply increase chip production.

Intermediary or end user?

Importantly, the key anonymous customers that Nvidia designates as Customer A, Customer B, etc. are not fixed from one accounting period to the next. Nvidia keeps their identities a trade secret for competitive reasons, but they can and do change locations. These customers certainly don’t want investors, employees, critics, activists, and rivals to be able to see exactly how much money they’re spending on Nvidia chips.

For example, the party designated as “Customer A” purchased approximately $4.2 billion in goods and services during the past quarterly period. However, that percentage appears to have declined in the past, as the first nine months totaled no more than 10%.

Meanwhile, “Customer D” appears to have done the opposite, reducing its purchases of Nvidia chips in the past fiscal quarter, but still accounting for 12% of year-to-date sales.

Their names are secret, so it’s hard to know whether they’re intermediaries like the troubled Supermicrocomputer that supplies data center hardware, or end users like Elon Musk’s xAI. is difficult. For example, the latter came out of nowhere and built a new Memphis computing cluster in just three months.

Nvidia’s long-term risks include moving from training to inference chips.

But in the end, only a handful of companies have the capital to join the AI race, as training language models at scale can be cost-prohibitive. Typically these are cloud computing hyperscalers such as Microsoft.

For example, Oracle recently announced plans to build a zettascale data center equipped with more than 131,000 of Nvidia’s cutting-edge Blackwell AI training chips. This will be more powerful than any individual site that ever existed.

It is estimated that the power required to run such a large computational cluster is equivalent to the output capacity of approximately 20 nuclear power plants.

Singh, the Bloomberg Intelligence analyst, sees little long-term risk to Nvidia. First, some hyperscalers are likely to end up reducing orders and diluting their market share. One such strong candidate is Alphabet, which has its own training chip called TPU.

Second, its superiority in training cannot be matched by inference, which runs the generative AI model after it has already been trained. Here, the technical requirements cannot be called cutting-edge. That means more competition, not only from rivals like AMD, but also from companies like Tesla that have their own custom silicon. As more companies leverage AI, inference will eventually become a more meaningful business.

“A lot of companies are trying to focus on that inference opportunity because they don’t need high-end GPU accelerator chips for that,” Singh said.

Asked whether this long-term shift to inference is a bigger risk than ultimately losing market share in the training chip market, he said, “Absolutely.”